Tidal Disruption Events

When a star passes within the Roche limit of a SMBH, it is pulled apart by the BH's tidal field in a tidal disruption event (TDE). These rare events are unique astrophysical probes of quiescent SMBHs, accretion physics, and the dynamics of the galactic center. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) promises to dramatically increase the observed TDE rate, making this an exciting time for TDE modeling.

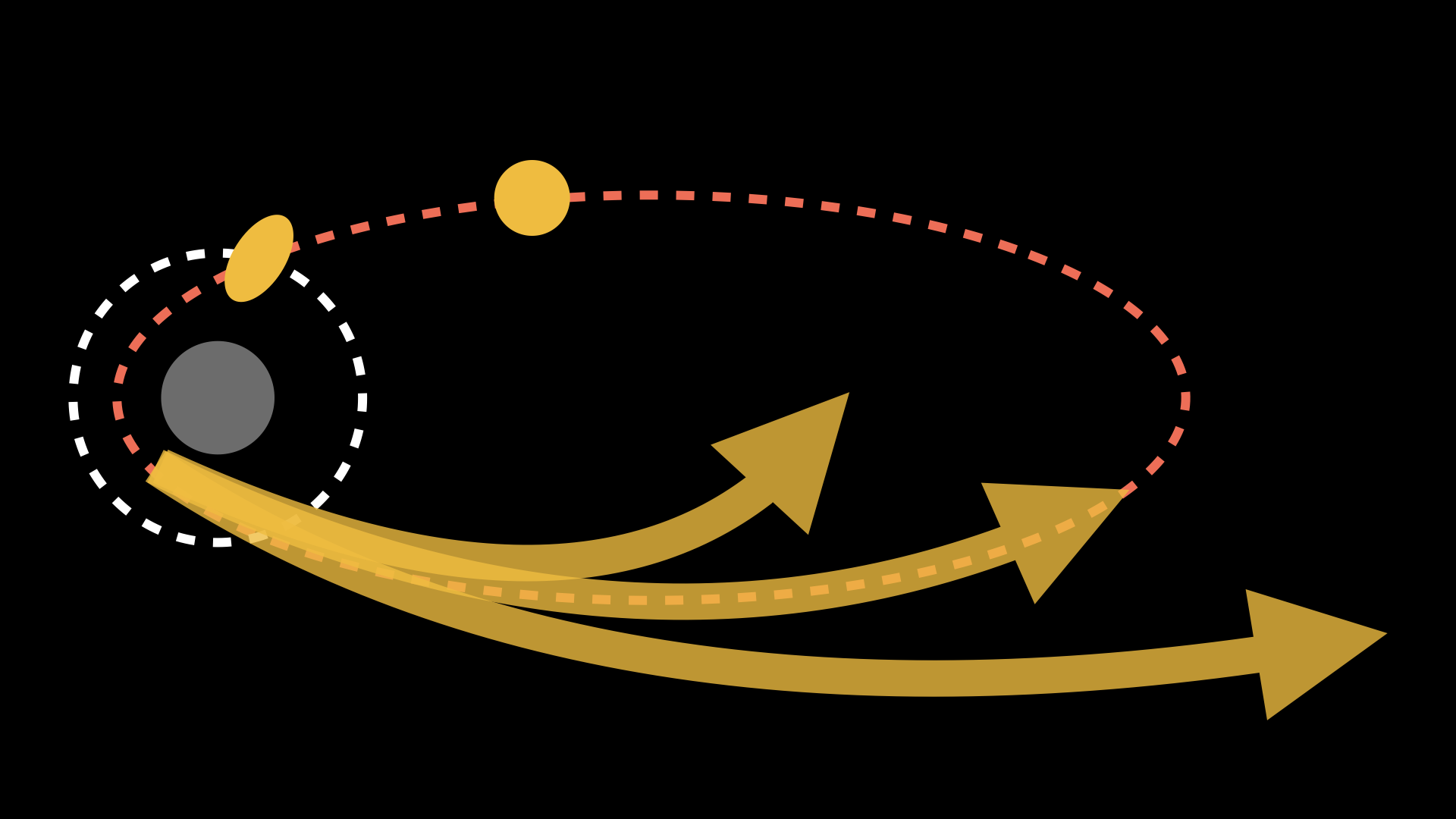

I use numerical simulations and (semi-)analytics to study the physics behind TDE emission. Ultimately, TDE emission is powered by the circularization and accretion of bound stellar debris, which falls back to the BH on eccentric orbits as a thin debris stream. Circularization is driven by stream-stream collisions induced by relativistic apsidal precession and, once a disk forms, interactions between the stream and the disk. These processes are affected by ballistic dynamics, chemical processes (e.g. Hydrogen recombination), relativistic nodal precession, and extreme vertical compression as the debris passes pericenter, which produces a nozzle shock.

In [1], I perform one of the first simulations of debris disk formation in a realistic TDE using the GRMHD code H-AMR, although these simulations are limited to a small fraction of the peak fallback time. In my ongoing work [2], I develop an idealized model to study the role of the nozzle shock in detail, including the effect of chemical processes and the implications for the stream self-intersection.

Cosmic Dawn Galaxies

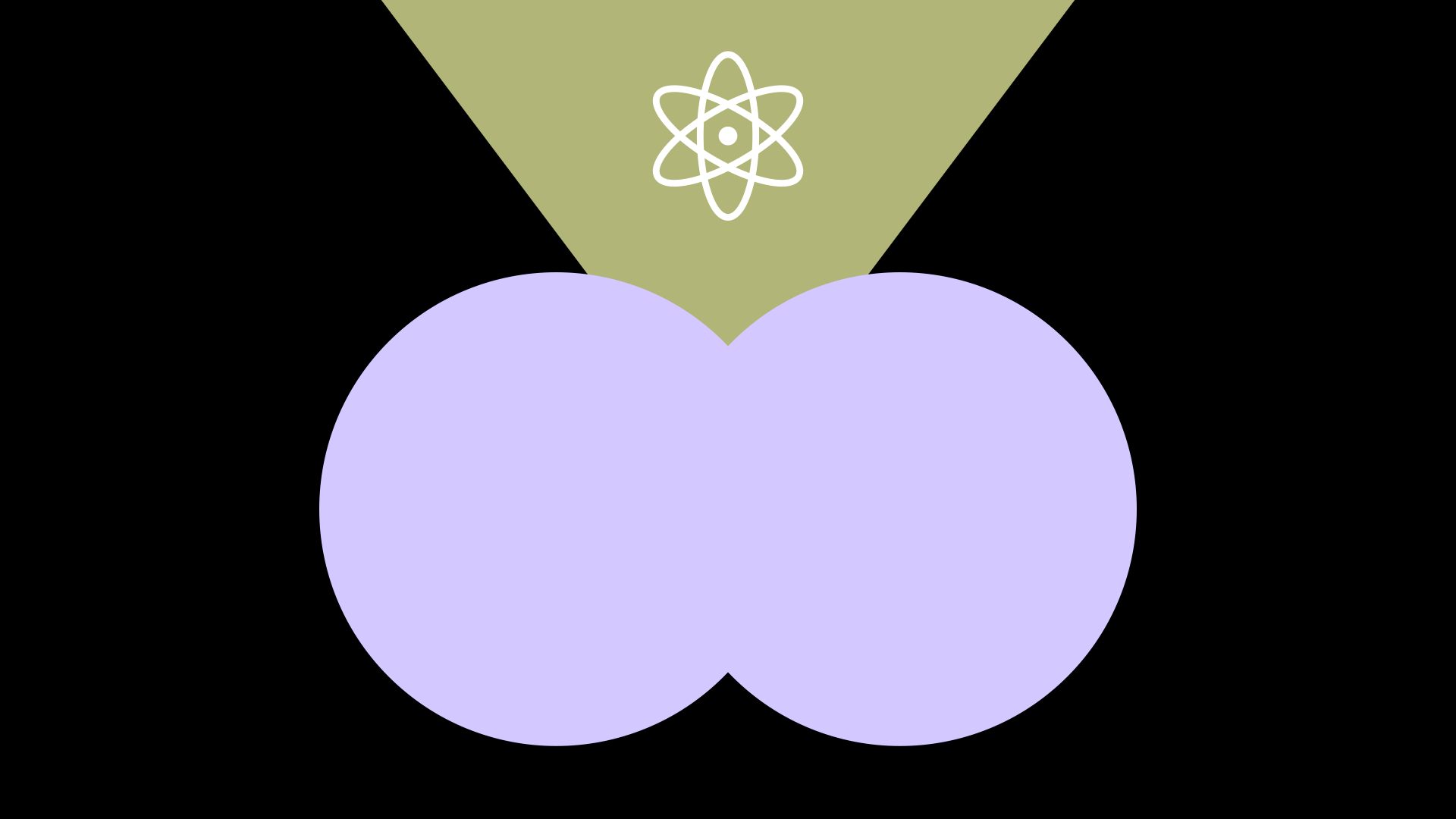

The JWST has opened a new frontier for empirical constraints on galaxy formation models at Cosmic Dawn (z>9), an epoch starting with the formation of the firststars and ending with the reionization of the intergalactic medium (IGM). JWST has discovered a growing list of galaxies at Cosmic Dawn with high stellar masses >1e8 Msol and/or high SFRs >1 Msol/yr, in tension with the expectations of standard galaxy formation models, and overmassive SMBHs relative to the local BH-stellar mass relation. I study the interplay between star formation, feedback, and BH growth in these unique environments, with extreme gas surface densities and intense accretion of cold streams.

In [1], I run cosmological zoom-in simulations of a massive galaxy at Cosmic Dawn, using a physically-motivated star formation recipe, which avoids ad hoc extrapolation from lower redshifts. In [2], we add SMBHs to these simulations to study their co-evolution with the galaxy.

Kilonovae

The observation of GW170817 confirmed that binary neutron star mergers are not only strong sources of gravitational waves, but also sites of nucleosynthesis by the rapid neutron capture process (r-process). The radioactive decay of r-process nuclides in the merger ejecta produces energetic gamma-rays, beta and alpha particles that, when thermalized, power a bright transient in the optical and near-infrared known as a kilonova (KN). In my ongoing work [1], I develop a new model for the transport and thermalization of beta decay electrons using the two-moment method and detailed electron-atom cross sections.

Miscellaneous

Optical Tweezer Arrays

Optical tweezers are micrometer-sized optical traps obtained by tightly focusing a laser beam. Optical techniques can diffract the beam into many spots, making it possible to form arrays of atoms in a variety of geometries. In such an array, the interactions between atoms can be controlled by inducing quantum tunneling between array sites or by placing atoms into high-energy Rydberg states. This property makes them great analog quantum simulators (AQS), i.e. a controllable quantum system that mimics a less experimentally feasible one via a direct mapping between their Hamiltonians.

As part of Nir Navon's Ultracold Quantum Matter Lab, I worked on an apparatus to cool bosonic Sr to nano-Kelvin temperatures so that it could be captured by optical tweezers. My main contribution was the design and construction of a control box for the electromagnetic coils of a magneto-optical trap (MOT). The MOT uses a quadrapole magnetic field and a set of counter-propagating lasers slightly detuned from an electronic transition to create an effective damped oscillator potential. Once the atoms are trapped, the MOT coils switch to a Helmholtz configuration to generate a strong ~700 G magnetic field to allow Sr's usually forbidden S - P clock transition.

My control box switches between these configurations rapidly using insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs) to operate a fast-switching H-bridge drawing up to 300 A. The control box also includes a water cooling system, a temperature interlock, and a custom printed circuit board for running the control box from a digital display. Aside from the control box, I also contributed the development of a new user interface for the parametric experimental control software Artiq, the application of convolution neural networks to the fast sorting of atom arrays via the assignment problem, the deployment of a network of sensors to monitor ambient lab conditions and log the data to an online database, and the alignment and testing of a double-pass acousto-optic modulator (AOM).

CubeSat

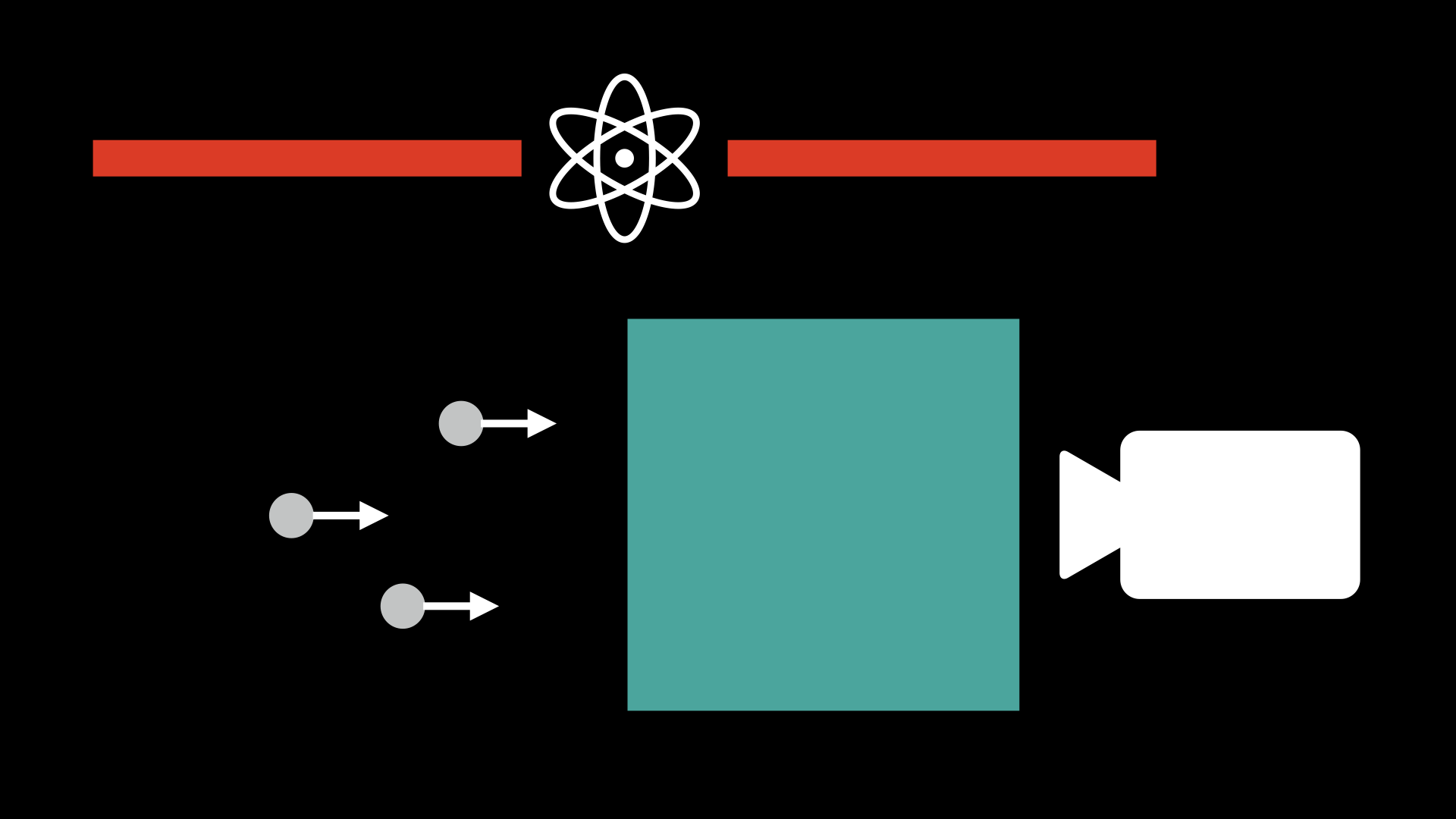

During my senior year of undergrad, I was president of the Yale Undergraduate Aerospace Association (YUAA), Yale's largest undergraduate engineering organization, with more than 80 members and several concurrent aerospace projects. In 2018, YUAA received a grant from NASA's CubeSat Launch Initiative (CSLI) to develop the Bouchet Low Earth Alpha-Beta Space Telescope (BLAST), a 2U CubeSat with a cosmic ray detector payload, to be launched into Low Earth Orbit (LEO). BLAST's main science objective is to detect high energy protons and map the changing morphology of the South Atlantic Anamoly (SAA), a region where the Earth's lower Van Allen Belt crosses LEO resulting in increased magnetic and charged particle fluxes. The SAA impacts satellites by interfering with astronomical observations and producing memory errors through bit flips. BLAST includes multiple interacting subsystems, including a gravity gradient boom and magnotorquers for attitude determination and control.

I lead the design of the cosmic ray detector (CRD) payload. The CRD consists of a plastic scintillator and a Silicon photomultiplier (SiPM). The signal from the SiPM is processed by several amplification stages and a custom multi-channel analyzer before count data is fed back to the on-board computer. The project was funded in part by the Connecticut Space Grant Consortium and we presented our progress at the Connecticut Space Grant expo.

I also worked on several smaller projects during my time with YUAA. During my first year, I worked on a team designing the rover payload for a rocket, to be flown at the Intercollegiate Rocket Engineering Competition (IREC). During my second year, I lead a small team designing and constructing an ornithopter, or robotic bird, capable of self-correcting flight. The ornithopter used high-torque servos to flap wings made of carbon fiber rods and kite fabric. By applying different offsets to the flapping cycle of the wings, we independently controlled roll, pitch, and yaw. The ornithopter included a custom printed circuit board which monitored acceleration and magnetic fields to calibrate steering and apply real-time corrections to its flight.